The notion of stewardship has increasingly become synonymous with family businesses. Being a “steward” no doubt resonates with those who see themselves as “baton-holders,” a term that has long been used by leaders of multi-generational business families.

However, many who label themselves as stewards are often not able to specifically describe the practice and their own development. Most stewards are likely not aware that stewardship has a rich theoretical pedigree, which is gaining increased attention from the researcher community. But, in the practitioner community, the term theory is too often relegated to the nether realms of unworkable concepts.

Kurt Lewin is credited with the phrase: “there is nothing as practical as good theory” and stewardship, the theory, is arguably the most practical family business theory.

Stewardship Theory in Practice

Many scholars have employed the concept of stewardship, not the theory, to describe the behavior of family businesses. Typically, they enlist proxy measures, such as executive compensation or attitude towards the natural environment, to establish differences between family businesses and non-family businesses.

Such proxy measures have been enlisted because, up until recently, there was no valid and reliable metric for measuring stewardship. In the March 2017 edition of Family Business Review, a paper will appear that introduces a Stewardship Climate Scale. The scale was developed from the seminal stewardship work by Davis, Donaldson and Schoorman (1997).

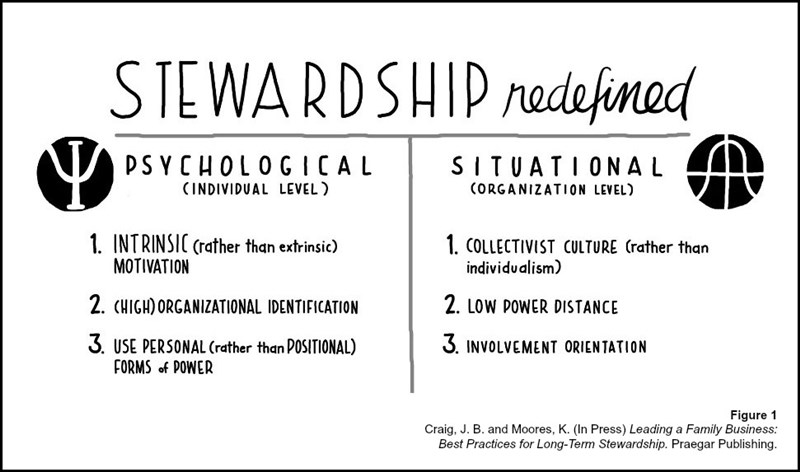

Their work helps us understand that stewardship, the theory, has two dimensions: psychological (individual level) and situational (organizational). Each has three sub-dimensions (see Figure 1).

Put simply, a stewardship climate is one in which individuals are more likely to be intrinsically rather extrinsically motivated, identify highly with the organization, and use personal, rather than positional, power.

In addition, at the organizational level, family businesses displaying stewardship climate are those with a collectivist culture, rather than an individualistic culture, have a low power distance, between positions, in their organizations and have a high involvement orientation.

Therefore, the presence of stewardship is recognized when individuals and organizations display these characteristics in the way they operate. While these are qualities we can all recognize in action, they are more elusive to measure. Our ability to develop and reward any behavior is dependent on our ability to measure it in some degree.

Measuring Stewardship in Action

The argument is that family businesses are more likely than non-family businesses to demonstrate a stewardship climate. With the validation of the “Stewardship Climate Scale” it is possible to support and better explain this widely accepted conclusion.

The ability to measure stewardship climate dimensions, as well as enabling differences between family and non-family businesses to be determined, make it possible to establish differences among family businesses in their ability to put this powerful asset into action.

Understanding the dimensions makes it possible to establish the extent to which a stewardship climate exists. This is important as the scholars who introduced the stewardship climate scale also established performance benefits of firms with greater stewardship climate.

To illustrate, consider first the individual sub-dimensions of stewardship and how you may frame questions to family and/or non-family stakeholders, such as:

- To what extent are individuals intrinsically motivated? Is this just a job?

- Do our people genuinely identify with the organization? Do we tell this story?

- As we have grown, and have designed more complex organizational structures, do we increasingly rely on positional power to get things done?

The message here is that you do not have to rely on the survey instrument, per se. By understanding the dimensions of stewardship climate you can then design questions to establish the extent to which stewardship is manifested by the individuals in your families and or businesses. Then, consider also the same exercise in the organizational context, and frame questions such as:

- If culture is so important to our competitive advantage, to what extent does it manifest as being collectivist rather than individualistic?

- Are our family and business leaders approachable? Is there in fact a low power distance in our organization, or have we lost this as the family and the business have grown?

- What tangible examples are there that we are in fact an organization that celebrates involvement?

Measuring Stewardship in Business and Family

Again, by using the organizational dimensions of stewardship the theory, it becomes relatively easy to frame practical questions to provide insight and guidance for a family business.

Stewardship dimensions would also be useful in developing meaningful human resource (HR) performance metrics. Given that any HR performance metric needs to be reliable and valid, it would seem appropriate to use a theory-driven evidence-based measure to establish, drive, and reward behavior across your organization and your family.

There are caveats to this related to the strategy being pursued, the life-cycle of the business and the family, culture, for example. Regardless, there would be benefit in linking performance to something that has been established as being a distinguishing characteristic of family firms and, importantly, which has been demonstrated to have innovation-related performance benefits.

Stewardship, the notion not the theory, can also be useful to frame other conversations. In multi-generational family firms where the potential for wide variations of commitment levels is heightened, there is a constant need to revisit the utility gained from being in business as a family. In such instances, for example, the concept of stewardship could be used to describe and understand the different perspectives. Consider asking this simple question:

What are we stewards of?

Likely the answers will be diverse. Good! Having this type of conversation will help those in decision-making positions make better decisions.

When the answer to the question above includes something that is intangible (hard to measure) such as a reference to an “emotional asset” or “legacy” (as in “We are stewards of an emotional asset” or “We are stewards of our forebear’s legacy”) there is likely to be need to clarify what in fact it means to be a steward. Prepare for different perspectives from different family members dependent on their generation and their understanding of what it means to be a member of the business and the family.

Conclusion

Finally, don’t be surprised that those not from the family (particularly long term employees) may feel more like stewards than some family members. And for that reason, it should be important to better understand stewardship the theory, such is its wide reach and practicality. This also presents an opportunity to reinforce that “there is nothing as practical as a good theory”…and finally suggest that stewardship is a very, very good theory for family business success.

Further Reads

• Davis, J. H., Schoorman, F. D., & Donaldson, L. (1997). Toward a stewardship theory of management. Academy of Management review, 22(1), 20-47.

• Marrow, A. J. (1977). The practical theorist: The life and work of Kurt Lewin. Teachers College Press.

• Neubaum, D. O., Dibrell, C., Thomas, C., & Craig, J. B. (2017) Stewardship climate: Scale development and validation. Forthcoming Family Business Review.