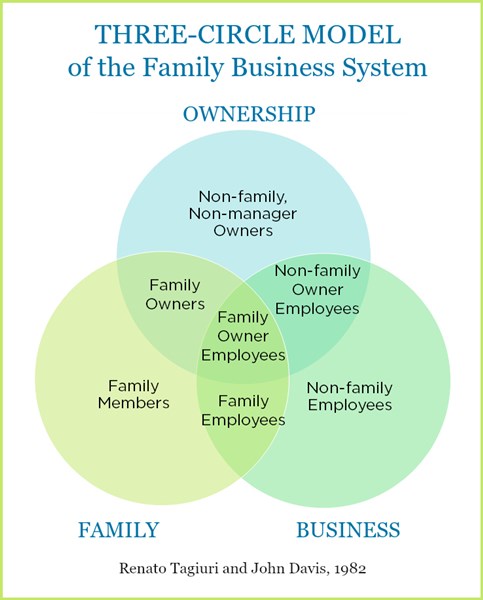

The 3-Circle Venn depiction of family business is ubiquitous and universally accepted as the way to define business-owning family challenges and opportunities. This framework is also useful in driving governance conversations. Typically, these conversations are centered on family governance and business governance. Ownership, while arguably the most important (and sensitive) of the three systems, is not given as much attention on the governance agenda.

The ownership system, like family and business systems, is heterogeneous. Some owners are operating owners, taking part in the management and operations of the business. Others are governing owners, focusing mostly on the rule and control of the business. There are also those who are investing owners, who hold shares in the firm while allowing the management and board to carry out what needs to be done. Some owners can be categorized by their degree of psychological ownership or emotional ties. Some are concerned with economic returns (i.e., dividends) while others see their stake as an emotional asset, with the return on an emotional asset being pride. Put another way, individual owners can be defined by the varying degrees of utility they receive from being owners. And, importantly, this changes over time.

Regardless, the overlap of ownership and control creates two critical challenges for the owners:

- How to be watchful and contribute to the family enterprise

- How to forge a consensus and common voice of family ownership opinion

Put simply, the real need for active family business owners is to create an optimal balance of ownership, family, and management, and to foster and enhance positive family-business relations.

Popular consensus is that family business owners have four broad responsibilities:

- To define the values that shape the company’s culture by having regular sessions with the managers

- To set the vision that establishes the parameters and boundaries for management strategies

- To specify the financial targets around growth, risk, liquidity, and profitability that the board can evaluate for feasibility and consistency

- To elect the directors and design the board

The unification of ownership and control calls for the establishment of family governance structures and processes in order to add value to the business, particularly in fostering positive business-family interaction. So, perhaps the reason why owners’ governance is not presented as a separate topic lies in the fact that ownership responsibility, properly discharged, requires the oversight of the governance structures and processes of the family and the business.

Family Governance Structure and Process

What family governance structures and processes should be in place for family firms? For some family firms, especially those still in the founder stage, the usual practice is for family leaders to make family governance decision themselves, without consulting other members. Some founders poll the family, asking them what they think, and make an informed decision thereafter. As the family grows, there is generally a need for structures, either formal or informal, to deliver family governance in the firm, providing education and fostering communication within the family business. This can be achieved through holding family meetings, convening a family assembly, or establishing a family council, with the support of a family charter or constitution.

The Family Council is the governance body focusing on family affairs. It serves the family, just as the board of directors serves the business. The role of the Family Council is to promote communication among family members and to provide a forum for the resolution of family conflicts. Moreover, the Council supports the education of next-generation members.

A Family Assembly is useful when the size of the family prevents all from sitting on the Family Council. An annual assembly operates in conjunction with the family council. Even if only convened once a year, the Family Assembly is another vehicle for education, communication, and renewal of family bonds. Through the Assembly, family members are given opportunities to participate and learn about the family business.

To govern the relationships between the owners, family members, and managers, a Family Charter (or Constitution) can be developed. The document explicates some of the principles and guidelines owners (shareholders) will follow in their relations with each other, other family members, and managers. The Family Constitution usually has no legal bearing, but can refer to documents that do (company constitution, buy-sell agreements, and the like). Importantly, in drafting a Family Constitution, no amount of legal expertise can match the goodwill and personal responsibility of family members.

Business Governance Structure and Process

Introducing business governance initiatives is not without its challenges. For example, the leader of a substantial family business told me his father’s reply when he told his father they should modify governance structures and processes, including adding independent directors: “Certainly, son. I welcome your proposal. Please, when you submit it, be sure to attach your letter of resignation.” It will surely take time to get the incumbents’ buy-in. But as another wise soul reminisced, “I should have done it [bring in independent directors] much sooner.” Still, another said, “It is a no brainer…takes the pressure off me to have people who the family trusts to help me guide the business…and besides everything else you may hear…if you want to sleep well at night and get along with your family members, put independent directors on your board.”

Recent evidence about boards and performance tends to substantiate the principles of independence of thought and accountability. Specifically, there’s still no direct link between systematic governance structure and financial performance, but growing data on how the effects of board structure and composition on firm performance are more indirect and complex. So the processes by which directors interact with one another has become the focus. Specifically, we now know how structure, group processes, and outside directors in family firms positively affect board processes: a greater proportion of outside board members is associated with higher levels of effort norms and board cohesion — board-level processes that are likely to enhance board effectiveness. That is, boards with outside directors are perceived as more committed to the board’s tasks (i.e., higher effort norms) and are more cohesive. Also, the boards of larger and older family companies demonstrated more clearly than those of other family firms the positive effects of outside directors on effort, cohesion, and use of knowledge and skills.

So when owners appoint independent directors to the board of their family business, a priority is to examine closely their ability to promote accountability and their ability to generate new ideas and challenge the board’s strategic plan. With these selection criteria, the family board is more likely to show higher levels of effort norms and board cohesion, which in turn will result in a more effective board. In time this should positively influence broader enterprise performance.

Many owners are reluctant and question the cost of this “additional” governance. Those who have pursued these initiatives typically attest that it is the cheapest advice they can buy. They advise to not focus on the cost; focus on the benefit(s). Even a single insightful direction from an independent director will repay his/her fees many times over. Having independents on the board changes how owners discharge their duty as stewards, which ultimately makes them more accountable for their decisions and that message builds trust and cascades through the business and the family.

The other question owners ask is “How many independents is the right number?” The answer to this question is “Ultimately, no fewer than three” — but this is an evolutionary process. It takes time to get governance systems and structures in place (in the family and the business) in order to attract high-caliber independents, and typically the journey starts with an advisory board. It takes time for everyone in the three systems to get comfortable with the idea of sharing information with outsiders, and an advisory board will smooth the way to a more formal, fiduciary board.

Why three independents? Basically, this will ensure there is a quorum to discuss issues and, from a logistics point of view, there will almost always be two independents present for board meetings (schedule conflicts often prevent one independent from joining quarterly meetings). Having at least three is also helpful when, inevitably, board members retire. If planned correctly, succession in the boardroom is not an issue and individuals can smoothly transition off the board, which is vital for regeneration of ideas as the needs of the business evolve.

“How many family members should be on the board?” is another common query. And, put simply, the answer is: “It doesn’t matter, as long as there are three independents.” But there is enough evidence to suggest that a board should be no more than eight members. True independents are rare. These guys leave any biases at the door and come prepared to every meeting to ‘persuade and be persuaded.’ They are keen thinkers who understand the family’s values and the business’s culture.

Conclusion

So, in sum, while governance of the ownership system may become a separate conversation at some point (typically in generation three and beyond), owners who are serious about, and committed to, their roles as stewards have a fundamental responsibility to drive and oversee the governance structures and processes of the family and the business to ensure communication and education in the family system and independence and accountability in the business system.

Adopted from Leading a Family Business: Best Practices for Long-Term Stewardship by Justin B. Craig and Ken Moores (2017), Praeger publishing.